It’s part of the universal human experience: to grieve someone we love. It happens when we least expect it, and when we’ve been expecting it for years. It happens to young and old, in ways that may feel violently unfair and unjust, and also in beautiful and sacred passings. And yet, our society still has so many ways in which ill-fitting platitudes, awkwardness, and avoidance show up when someone is grieving. We collectively still have much to learn about holding space and time for people who experience loss.

Let me qualify, I am not a grief expert. My “qualifications” here are those of a person experiencing her own grief following her dad’s death and as a former Head of HR who understands that a grieving employee will benefit from the support and comfort of the working community.

At work, we are asked to show up creative, inspired, and present. While work provides important meaning in our lives, it can also be a really hard place to be in grief. The world of work is on its toes, it moves quickly and with the expectation of efficiency. However, a grieving employee may not be ready to return following three days of bereavement and be ready to be “all in”, focused, and on task. They might still be struggling to get out of bed.

How do we support employees in their grief? It’s an important question, not only from the standpoint of getting the work done but from the equally important perspective of being there for another human who is hurting. Workplaces are made up of humans; humans have feelings; feelings have an impact on our functioning. As leaders and coworkers, the better equipped we are to see and honor the whole person, the more we create an environment of trust, rapport and engagement.

Here, I’ll offer a few ideas on how organizations can support an employee in the days, weeks, and months following a loss.

- Everyone experiences grief differently

Perhaps the truest thing about grief is that each person experiences it so differently. It can be complicated or not. It can feel profound and unfathomable and devastating or not. It can depend highly on the circumstances surrounding death, and it can also depend highly on the circumstances surrounding life. The very last thing we want to do as leaders and coworkers is to assume we know or understand how someone is moving through their grief. Words like, “I know how you feel,” or “I’ve been exactly where you are” are well intended, but you don’t, you can’t, know how someone else experiences it. People may make assessments of those circumstances, i.e., “she lived a full life,” or “he is no longer suffering,” or even “you’ll be okay because of your faith.” Trying to make sense of someone’s else circumstances is not supportive. We do this in large measure to feel better about our vulnerability surrounding death, and our fear that so much is not within our control.

- Ask the employee about communication preferences

At my former company, it was our practice to ask the employee if they wanted HR to send out a companywide email about the loss of a family member. The purpose of this was to allow our workforce to send sympathy notes or pay respects in person, but it served an equally important purpose of letting others know that work was not “status quo” for this employee. Many people welcomed that support and were relieved to have the information shared, and some preferred not. It is very useful to ask the employee what feels most comfortable. Perhaps they want their immediate team to know, but not other employees. Perhaps they want a key client to know because they are concerned about time out of the office. Engaging the employee in the conversation instead of getting ahead of their intentions will feel the most respectful and supportive.

- Don’t rush an employee out of grief

There is no typical timeline for grief. Society has this tendency to rush people back to regular life, to sweep them back into the motion as if busyness can somehow erase their awareness of the loss. It is unhelpful to manage to expectations about when or how someone should set their grief aside. It’s a passage, and it can take days, months, years, or a lifetime. It may be after the immediate rush of sympathy notes and meals and flowers and visitors that the weight of the loss sets in. The amount of time you may feel is “sufficient” to process death is untethered to the employee’s experience of it.

- Maintain equity, but honor cultural differences

If your organization has any norms, policies, or practices in bereavement, it is important to maintain equity in those practices (such as memorial gift values or bereavement leave), but also to recognize and honor differences in the way people grieve. Leaders aren’t necessarily expected to know these differences in cultures or religions, but this is why checking in with the employee is so valuable. They may explain to you that certain rituals or customs are honored; whether services are traditionally public or private; what roles bereaved family members play, or the expected period of mourning. If the employee is private, they may choose not to share, and that’s okay too. It’s about meeting the employee at their own level of comfort in making those details available.

- Check in frequently, not to “evaluate” how the employee is doing, but to meet them wherever they are

We often think of grief as something that needs to be managed. Grief is something to be felt, experienced, survived, and understood as a form of love. It’s unpredictable, and the idea that we can “manage” it like a project with a schedule is simply unhelpful and unfair to the employee. Employees who have always been loyal and hard-working will remain so, but they may require time and space to attend to the hardest part of their grief. If you can be there for them in grief, it may just be one of the most meaningful things you can do as an organization. They won’t forget that you showed up when they were hurting.

- Don’t avoid expressing sympathy out of fear

Sometimes coworkers fail to acknowledge the passing of a loved one out of fear, worry about what to say, or due to the intensity of the situation, such as a parent who loses a child. Grief is so intensely personal that we each have our worries about getting it wrong. For the most part, it’s better to show up in kindness than to hold back in concern about how your words or action are perceived. Your coworker will remember that you reached out, sent a sympathy card, hugged them, or offered to help cover during the days following their loss. If you aren’t sure what to say, ask them about their loved one.

- Talk to the employee about workload and balance following the loss

Your instinct as a boss or manager may be to let the person sit on the sidelines for a while, to assign less work to them, or keep them off a new business, an exciting client opportunity, or key initiatives. Here again, try to be aware of assumptions about what the employee may or may not be willing and able to participate in. For some, work is a welcome distraction and a constructive way to engage with the world during their grief. Still others go through the motions for some time before they can focus and thrive again. In either case, getting the employee’s input will be received as most supportive.

- Be aware of tools and resources to help the employee

Managers especially should be aware of the resources available to help grieving employees. These may include access to an EAP, knowledge of bereavement policies, access to mental health counseling through the insurance plan, and access to HR for discussions about wellness, coping, and if needed, a medical or personal leave.

The most meaningful way we can show up for our employees in grief is to let them know we are here, and then to follow through on being there.

It’s one of the most intensely personal of life milestones, and it’s also an inevitable part of being human. As leaders, coworkers, clients, and partners, let’s send the message: we honor how it feels to you. We can offer a much-needed pause for the employee to simply stop and acknowledge that someone else’s world has just stopped spinning. Our grief deserves its own space, and that space includes the workplace.

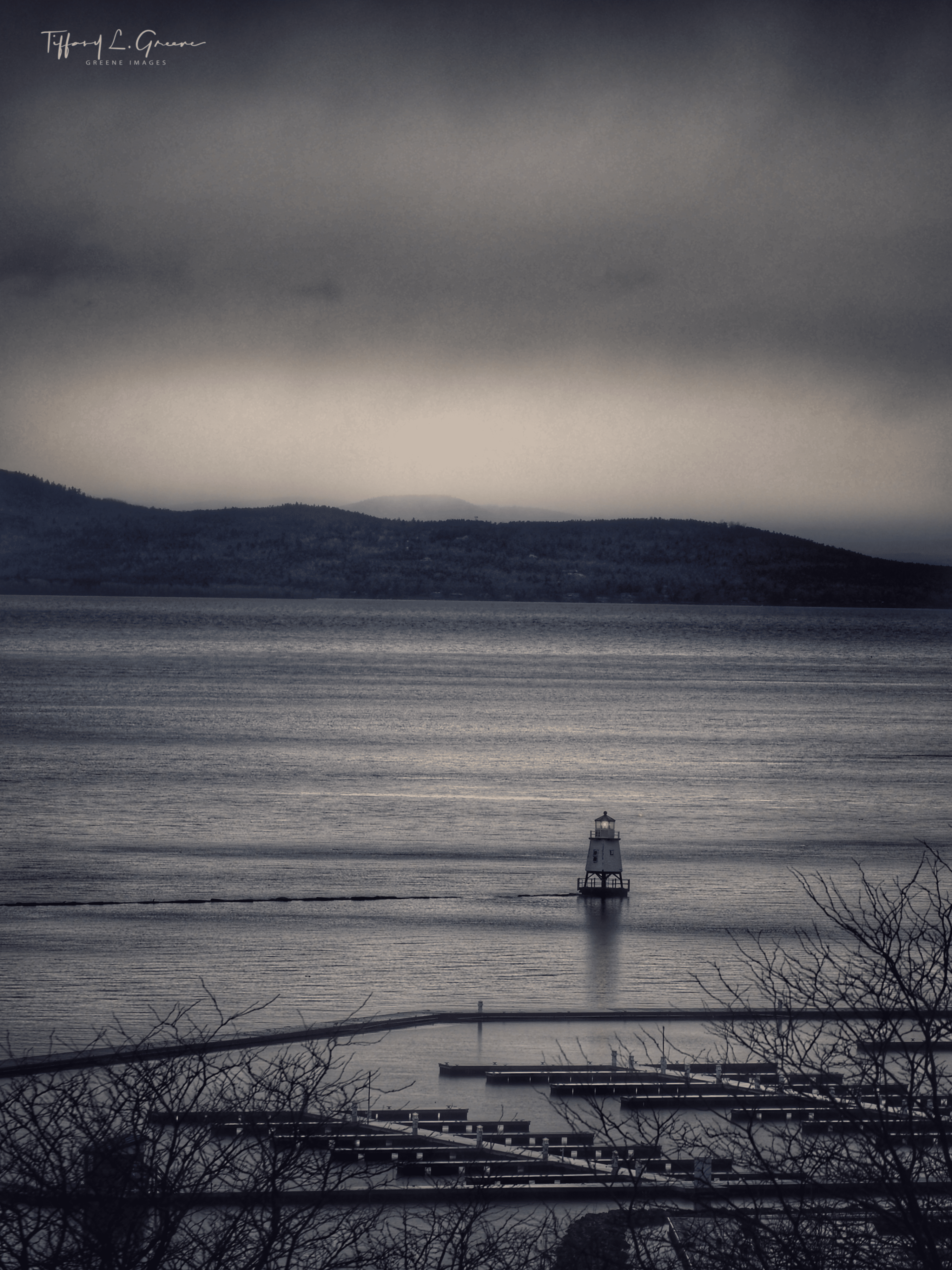

Image copyright Tiffany Greene

Tiffany Greene is a career and leadership coach. You can reach her at tiffany@greenecareercoach.com or at http://greenecareercoach.com